Choosing the right image file type is an often overlooked, but key aspect of image optimization. The importance of using performant yet high-quality images is also reflected by Lighthouse's Serve images in next-gen formats audit, which is one of its web performance signals designed to help developers and website owners improve user experience and web performance.

While serving images in next-gen formats is a huge opportunity to improve web performance, these new image formats are not always the best option. Sometimes you can be better off using other image file types. For example, the lossless versions of the WebP and AVIF formats have questionable performance results while lossy WebP and AVIF perform great.

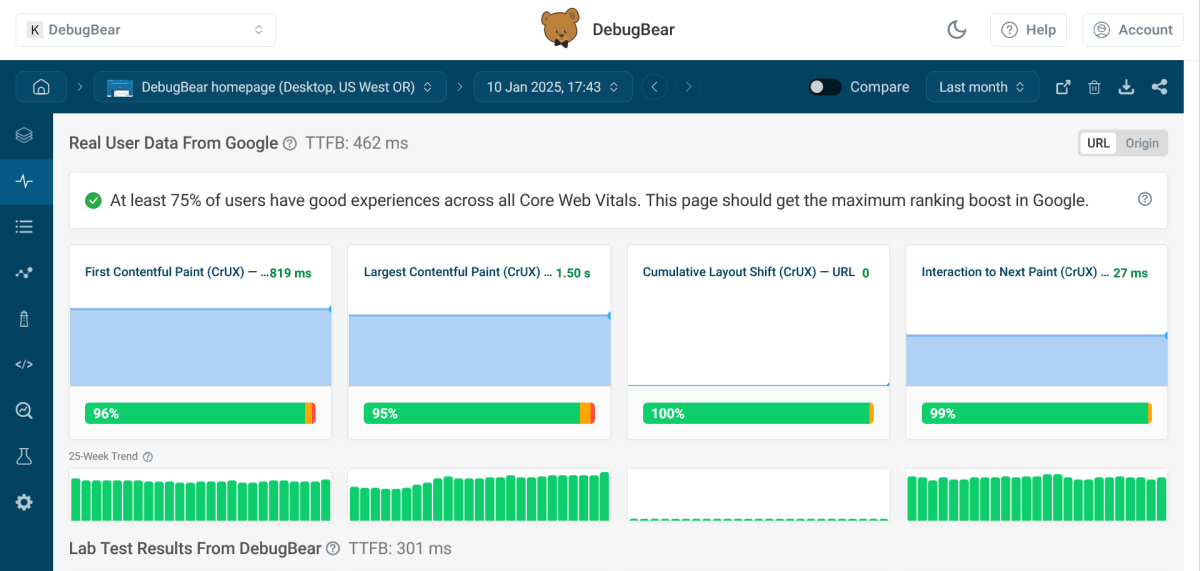

Finding the balance between aesthetics and speed is never easy on the web, and it becomes even harder when it comes to improving your image delivery. But, DebugBear is here to help you serve high-quality images while still achieving all-green performance scores:

This article is a comprehensive guide to image file type optimization for 2025 and beyond.

First, we'll look into the practical aspects of how to serve images in next-gen formats so that you can get started fast if you just quickly want to pass the Lighthouse audit. We'll also see whether you can safely use the WebP and AVIF image formats in modern browsers.

The second part of the article is for pros who want to understand the ins and outs of image file type optimization. Here, we'll explore the differences between lossy and lossless image compression, look into use cases for the six best-performing image file types (GIF, PNG, JPG, WebP, AVIF, and SVG) in detail, and see when to use which.

What Are Next-Gen Image Formats in Brief

'Next-gen' stands for 'next-generation'. Next-generation image formats aim to achieve smaller image sizes while providing advanced visual features, so they are great for both web performance and design.

Currently, the two widely supported next-gen image file types are WebP and AVIF, each offering both lossy and lossless variations (below, we'll see when to use each variation). To serve images in next-gen formats, you need to convert them to WebP or AVIF format.

There are some other next-gen image formats, too, with JPEG XL being the most advanced (it supersedes both JPEG 2000 and JPEG XR, the two other next-gen variations of the JPEG format). However, since Google Chrome removed support for JPEG XL, its browser support has fallen below 15%, making it no longer recommended for use on the web.

The removal of JPEG XL support is bad news for web performance, as it has a higher compression ratio than WebP and matches AVIF, while it adds several advanced features to JPEG (e.g. animations, layers, overlays, alpha channels, depthmaps, etc.). It offers photographic image quality and supports both lossy and lossless compression.

Now, before looking into how to serve images in next-gen formats, let's see one of the most important things when it comes to using anything new on the web ― browser support.

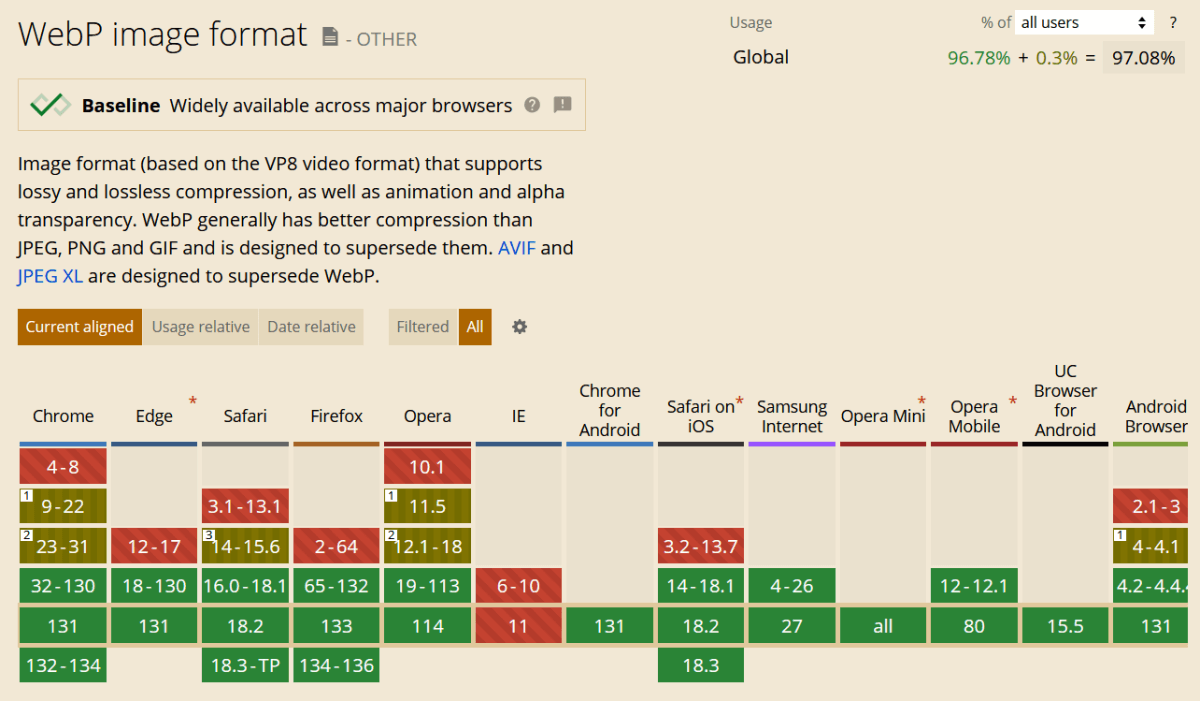

WebP Browser Support

WebP (Web Picture) is the most widely supported next-generation image format on the web. You can use it in all modern browsers. It has achieved the Widely available status of Web Platform's Baseline initiative (which is the highest of three stages).

For current WebP browser support, check out CanIUse's WebP page.

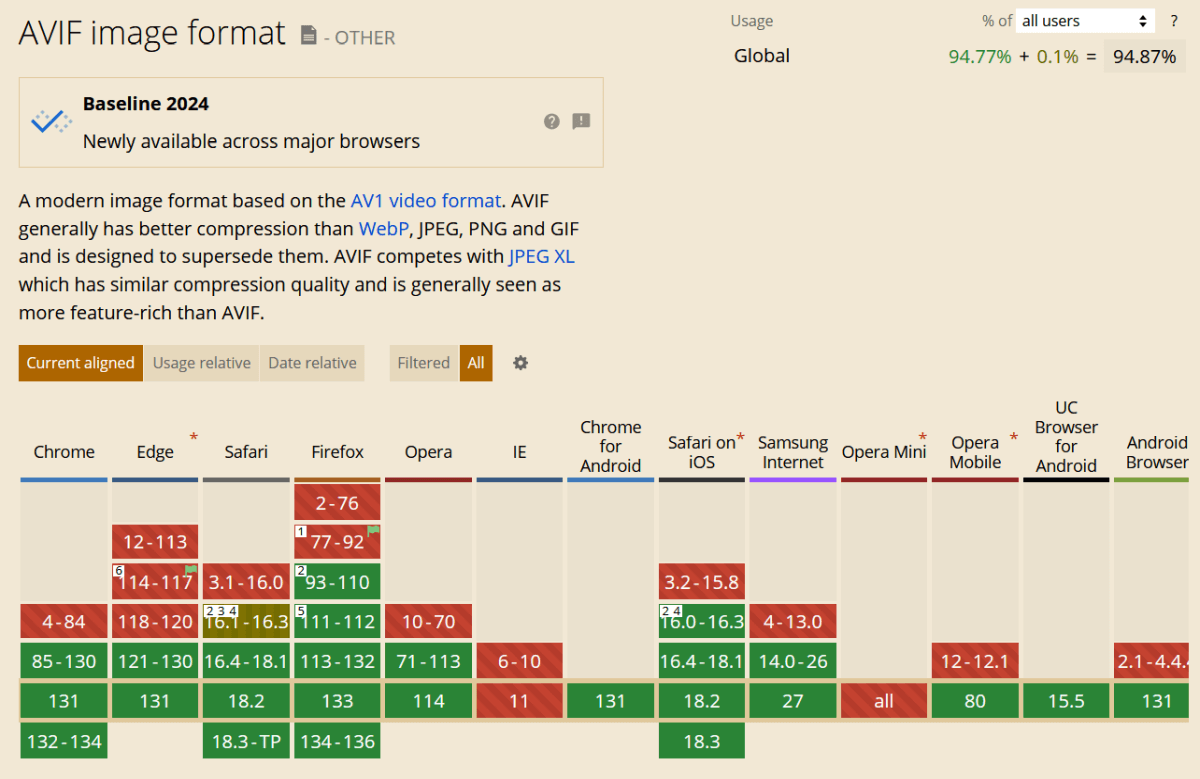

AVIF Browser Support

AVIF (AV1 Image File) is almost as well supported by modern browsers as WebP.

It's currently at the second, Newly available stage of Baseline. This means that it's already supported by all major browsers (i.e., it's interoperable), but it has been less than 30 months since it achieved this status (when it will become 'Widely available', like WebP).

For current AVIF browser support, check out CanIUse's AVIF page.

How to Serve Images in Next-Gen Formats

Now let's see how to serve images in WebP and AVIF formats on websites and in web applications.

1. Add Next-Gen Images to Your HTML Page

You can use the <picture> HTML element to add your images in both AVIF and WebP formats complete with a fallback to let the user's browser decide which file type to use.

For example, the code below first checks if the browser supports AVIF ― if yes, then it downloads the AVIF image; if no, then it checks if it supports WebP. If yes, it downloads the WebP image; if not, it downloads the JPEG fallback.

<picture>

<source srcset="images/avif/image.avif" type="image/avif" />

<source srcset="images/webp/image.webp" type="image/webp" />

<img src="images/jpeg/image.jpg" alt="Image" width="1280" height="960" />

</picture>

As now AVIF is also widely supported by browsers, you can omit WebP if you want (or, vice versa, you can only add WebP and JPEG if you prefer to use WebP as the primary next-gen image format on your website):

<picture>

<source srcset="images/avif/image.avif" type="image/avif" />

<img src="images/jpeg/image.jpg" alt="Image" width="1280" height="960" />

</picture>

If you don't need to support legacy browsers, you can also simply add the AVIF or WebP image within the <img> tag, without using <picture> and <source>.

2. Convert Images to Next-Gen Formats

To serve images in next-gen formats, you'll also need to convert them to WebP or AVIF.

These days, you have many options to choose from:

- You can save the image in the WebP or AVIF format in your image editing tool. WebP already has native support in most apps, such as Adobe Photoshop (since version 23.2). Native AVIF support is a more difficult question, but for major photo editing tools, third-party AVIF plugins are already available.

- To convert existing JPEG and PNG files to WebP or AVIF, you can use online image compression tools such as the Squoosh app by Google Chrome Labs or command line converters such as cwebp for WebP or avif-cli for AVIF.

- If you have a WordPress site, you can use an image optimization plugin to automatically convert your existing image files to next-gen formats, such as Imagify, ShortPixel, or EWWW Image Optimizer. WordPress has native support for WebP since version 5.8 and for AVIF since version 6.5, so you can use serve images in next-gen formats on a WordPress site without compatibility issues.

As discussed above, both WebP and AVIF have a lossy and lossless version. If you do manual image conversions, you'll need to convert lossy image file types, such as JPEG, using the lossy algorithms, while lossless image file types, such as PNG, using the lossless algorithms of these next-gen image formats. In the second part of the article, we'll look into the differences between lossy and lossless compression in detail.

3. Test If You Need to Serve Images in Next-Gen Formats

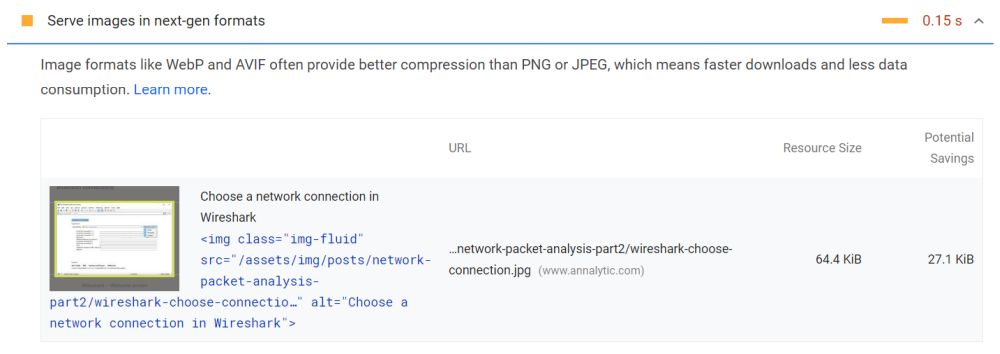

To see whether converting your images to next-gen formats is worth it, you can run a website test using Lighthouse.

Once the test completes, check your score for the Serve images in next-gen formats audit. If you have received the yellow or red flag, conversion to the WebP or AVIF format will mean a significant performance gain, as your images will be (much) more lightweight:

As I mentioned in the intro, lossless WebP and AVIF conversion is not always worth it, e.g. if your site mostly includes PNG images, using a PNG image optimizer can be a better option. (We'll see when it's worth serving images in next-gen formats in detail below.)

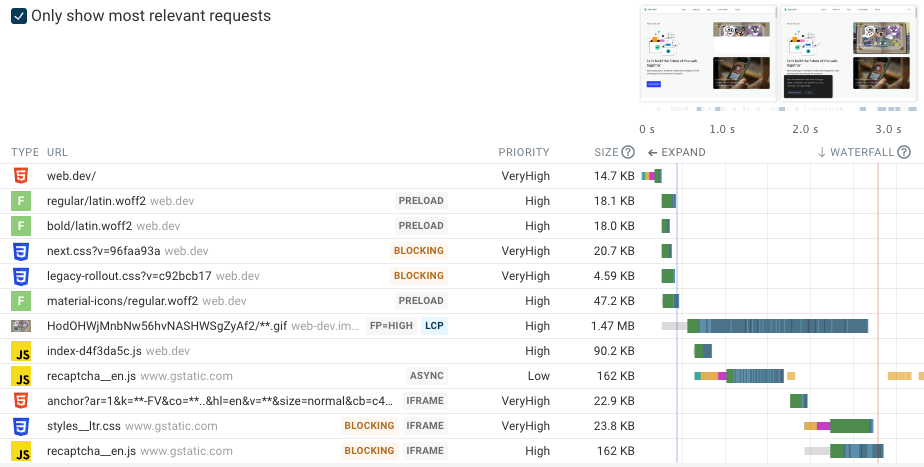

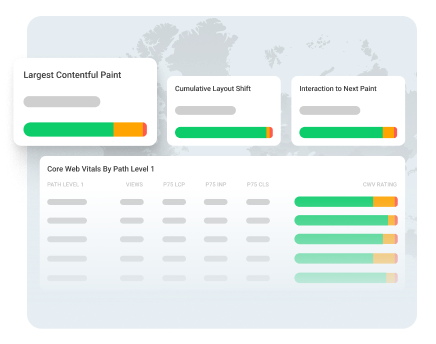

You can also test which images slow down your page using DebugBear.

You can use our free website speed test to see how image downloads are impacting your performance and Core Web Vitals, and find the ones that take the most time to download:

That's for the practical aspects of passing the Serve images in next-gen formats Lighthouse audit. Now, let's see the second part of the article that can help you decide whether you should serve images in next-gen formats and find the best file type for each image on your website.

Why Do Image Formats Matter?

Finding the right format for your digital images is important because each image file type comes with its own feature set, has its advantages and disadvantages, and serves specific use cases. Using less effective formats for many of your images can increase page load times, make your website less visually attractive, and harm the overall user experience.

Image file formats vary in:

- Scalability:

- Raster, also known as bitmap, images (e.g. PNG, JPG, GIF) are made up of pixels, so they cannot be magnified without losing quality.

- Vector images (e.g. SVG) are made up of geometric shapes, so they scale without any quality loss.

- Compression method (lossy vs lossless compression)

- Level of browser support

- Other characteristics such as support for different color depths, transparency, animations, etc.

Choosing the best file type for an image is about finding the balance between visual quality and performance (defined by the size of the image file).

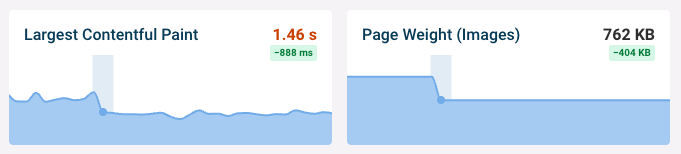

For example, at DebugBear, we were able to cut our hero image size from 171 KB to 94 KB and improve our Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) score from 2.4 to 1.5 seconds by switching from PNG to WebP format — see the drop in both LCP and total image weight on the screenshot below (however, other developers had different results when testing next-gen images):

Lossy vs Lossless Compression

Most raster image formats you can use on the web are compressed formats. They are reduced in size by a compression algorithm (also known as a codec), which removes non-essential and/or less important data from a file following pre-defined rules.

There are lossless and lossy data compression algorithms; next-generation images support both types.

Lossless Compression

Lossless compression algorithms only remove non-essential data (i.e., unnecessary metadata). As a result, they usually (but not always) generate larger-size files than lossy algorithms. However, there's no loss of quality (this is why they're called 'lossless'), and the compressed image looks the same as the original one.

Some examples of lossless data compression algorithms are:

- RLE (Run-Length Encoding)

- Huffman coding

- LZW (Lempel-Ziv-Welch) compression used by GIF images

- DEFLATE used by PNG images

Note that as these are general-purpose algorithms — they are not exclusively for image compression. For example, Huffman coding is used for compressing HTTP/3 headers, and DEFLATE is the basis of GZIP compression as well.

Lossy Compression

Lossy compression algorithms remove both metadata and essential data (less critical visual information), therefore they can achieve a higher compression ratio. While smaller image sizes improve web performance, lossy image compression comes with some quality loss — for instance, you can end up with pixelated images.

Some examples of lossy compression algorithms are:

- Fractal compression

- DFT (Discrete Fourier Transform)

- DCT (Discrete Cosine Transform) used by JPG images

Since this type of compression comes with information loss and quality degradation, lossy image formats include quality settings to allow the application or user to determine how much quality loss they are willing to tolerate in exchange for a higher compression ratio.

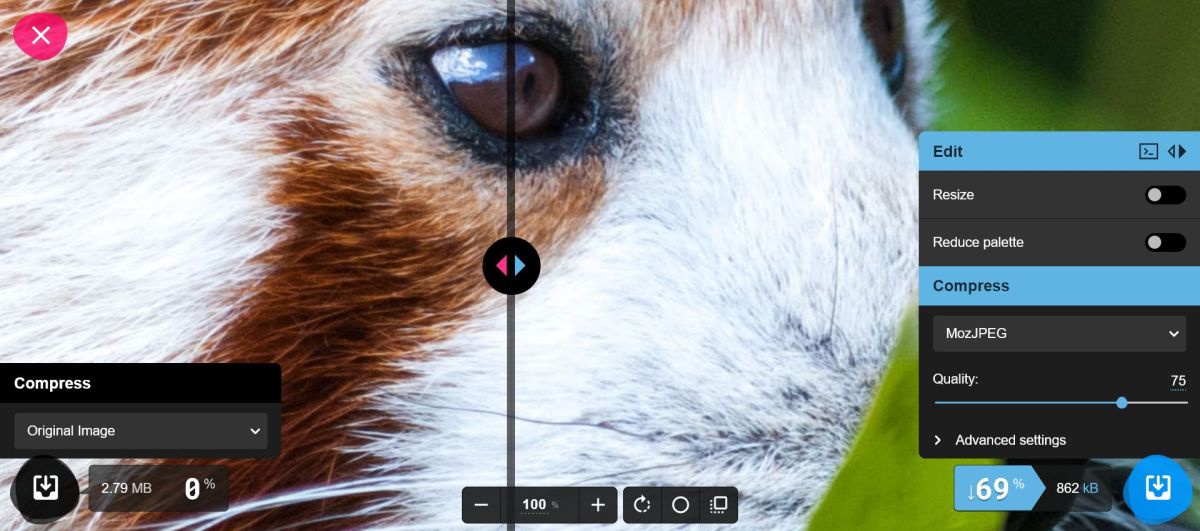

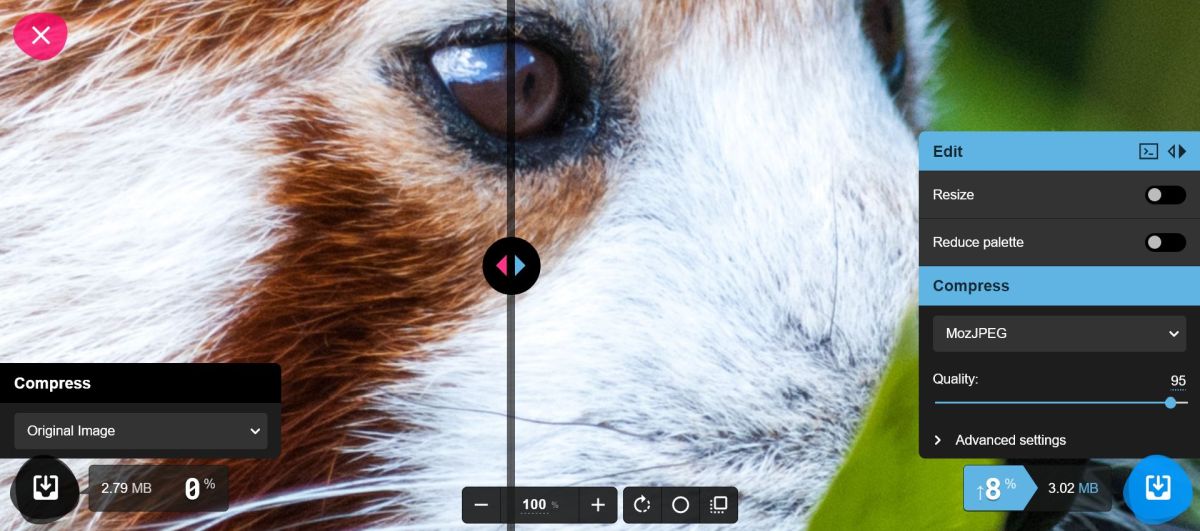

Higher-quality images usually (but not always) mean smaller file sizes. For example, when we set the quality ratio for this JPG image to 75% in the Squoosh app, we could reduce the file size by 69%:

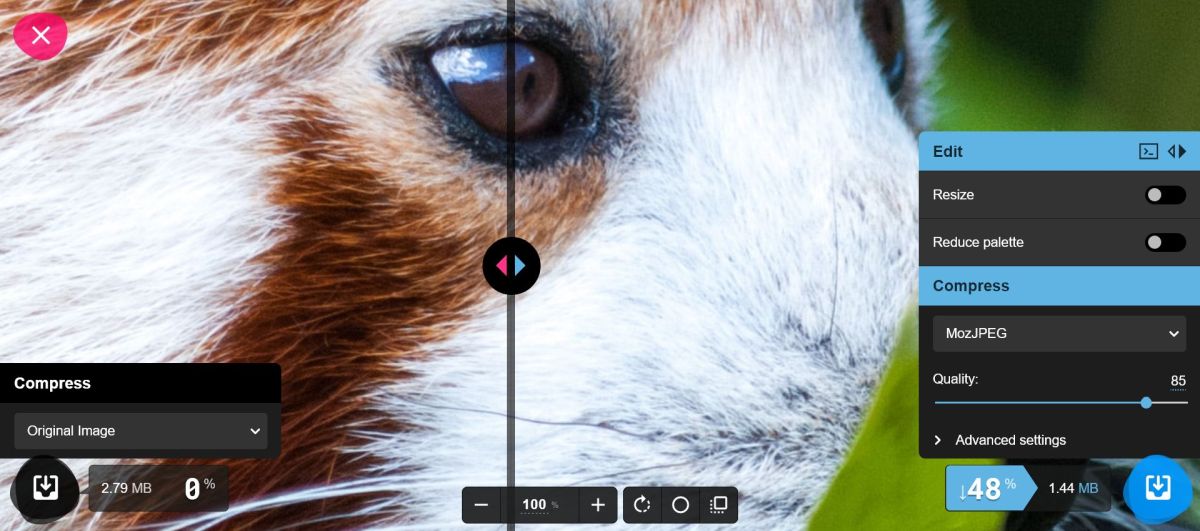

With a quality ratio of 85%, the compressed file was just 48% smaller than the original one — while the compressed image is a little bit sharper now, there's still not a huge difference in quality:

However, with a quality ratio of 95%, the compressed image is 8% larger than the original one — this is the ratio where lossy compression isn't worth it anymore:

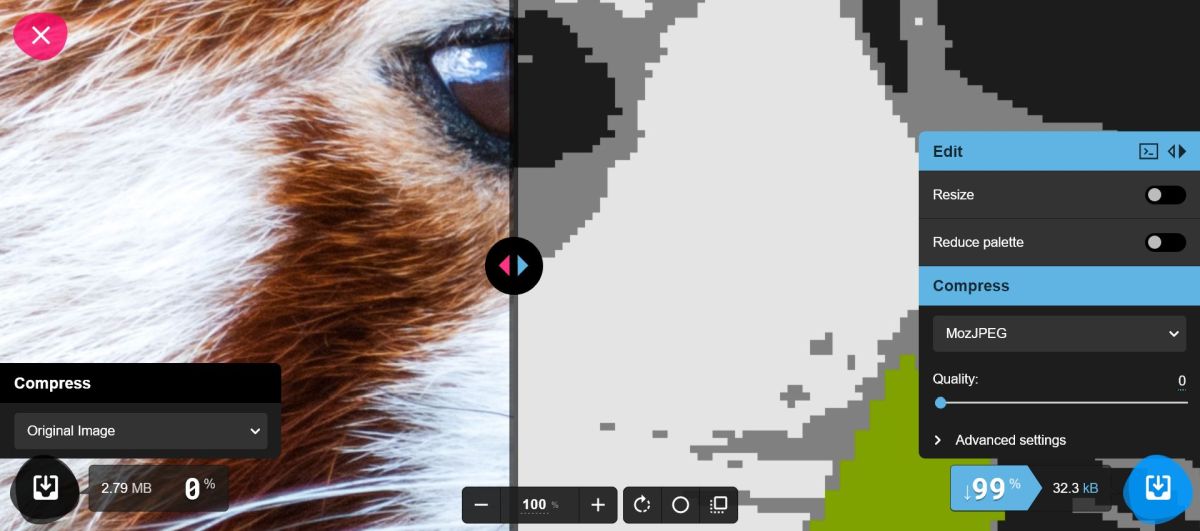

For reference, here's what the image looks like with a quality ratio of 0% — the color palette is reduced to the most basic colors, and the figure on the image becomes unrecognizable:

What Are the Best Image Formats for Web Use

To decide what image file types to use on your website and whether it's worth serving all your images in next-gen formats, let's see the six best formats for web images (i.e., GIF, PNG, JPEG, WebP, AVIF, and SVG), their key features, and when to use which.

There are other image file types that are supported by web browsers as well, such as the ICO format frequently used for favicons or the uncompressed BMP format, however they are not recommended for web content, as they have better alternatives.

GIF (Graphics Interchange Format) – Lossless

The GIF format was first released in 1987 with the aim to compress large image files to make them download faster. While these days it's best known for animated GIFs, it's actually a still image format, and animated GIFs are just flipbooks of multiple still GIF images.

As GIF was created in the era of the early web, it has fewer features than other image formats, however due to its relatively small size, it can help with performance optimization and still has a place in modern web development.

Key Features of GIF

- a lossless format for raster images

- uses the LZW compression algorithm

- 8-bit indexed palette (can only display 256 standard RGB colors on one image)

- supports basic, auto-playing animations

- supports one-level transparency (i.e., a pixel is either fully transparent or fully opaque)

- extensive browser support

Recommendations

- Use GIF for logos, grayscale photographs, and cartoon-style web graphics that are only made up of a few colors.

- Don't use GIF for high-resolution photos and detailed images that include more than 256 colors.

- While animated GIFs are popular, they're bad for web performance and accessibility, so consider replacing them with animations that can be stopped, e.g. short MP4 videos or animated SVGs.

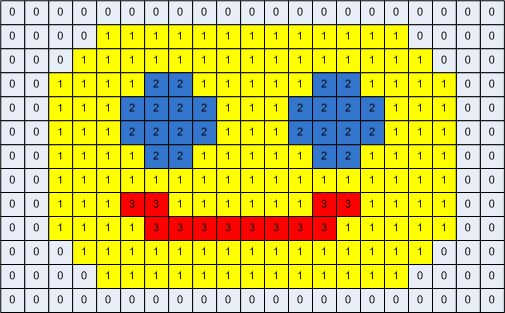

Image: The breakdown of a GIF file made up of four colors (credit: CommandLineFanatic.com – Inside the GIF file format)

PNG (Portable Graphics Format) – Lossless

The PNG format was created in 1995 to provide a non-patented alternative to GIF, as the LZW algorithm used for compressing GIF files was patented at that time (the patent expired worldwide in 2004).

PNG uses the non-patented DEFLATE algorithm, which is a combination of LZW and Huffman coding. It offers more visual features than GIF, including semi-transparency via the alpha channel and a much broader color palette.

Key Features of PNG

- a lossless format for raster images

- uses both pre-compression and the DEFLATE compression algorithm

- 24-bit color depth, also known as true color (8 bits per channel on the red, green, and blue channels), which is equal to 16,777,216 (256x256x256) colors in the standard RGB color space

- supports transparency and semi-transparency via the 8-bit alpha channel

- good text readability due to the lossless compression

- extensive browser support

Recommendations

- Use PNG for non-photographic images, logos or graphics with transparent backgrounds, and illustrations that include text such as screenshots, marketing banners, charts, or infographics.

- Don't use PNG for high-resolution photos, as it will result in a huge file size.

- You can use PNG as a fallback for the lossless versions of next-generation images.

Image: Transparent NASA logo in PNG format (credit: PNGEgg)

JPG/JPEG (Joint Photographic Experts Group) – Lossy

The JPEG standard was created in 1992 by the Joint Photographic Experts Group. They wanted to come up with a good-looking but lightweight digital format for photographic images. They introduced the concept of lossy compression for images, which is based on the science of how humans see, and removes high-frequency visual information such as hue and sharp transitions.

The JPEG format is associated with six file extensions: .jpg, .jpeg, .jpe, .jif, .jfif, .jfi (JFIF stands for JPEG File Interchange Format). There's no difference between them; they were created to support different platforms, but today.jpg is the standard extension.

Key Features of JPG

- a lossy format for raster images

- its compression method is based on the DCT (Discrete Cosine Transform) algorithm

- 24-bit RGB color depth (~16.77 million colors), like PNG

- allows applications to set the compression ratio

- comes with generational loss (the quality degrades with every modification to the image file)

- extensive browser support

- also has a lossless version called JPEG LS, but browsers and most image editing tools don't support it

Recommendations

- Use JPG for photographic images and photo-realistic digital graphics that don't include any text.

- Don't use JPG for icons, line drawings, and text-heavy images because JPG images have poor readability due to the lossy compression.

- You can use JPG as a fallback for the lossy versions of next-generation images.

Image: An example of a high-resolution JPEG photo (credit: Errin Casano, Pexels)

Image: An example of a high-resolution JPEG photo (credit: Errin Casano, Pexels)

WebP (Web Picture) – Lossy and Lossless

The WebP format was created by Google with the aim to replace GIF, PNG, and JPG with a more lightweight and flexible image format that has both a lossy and a lossless version. WebP was first announced on the Chromium blog in 2010, and its first stable version was released in 2018.

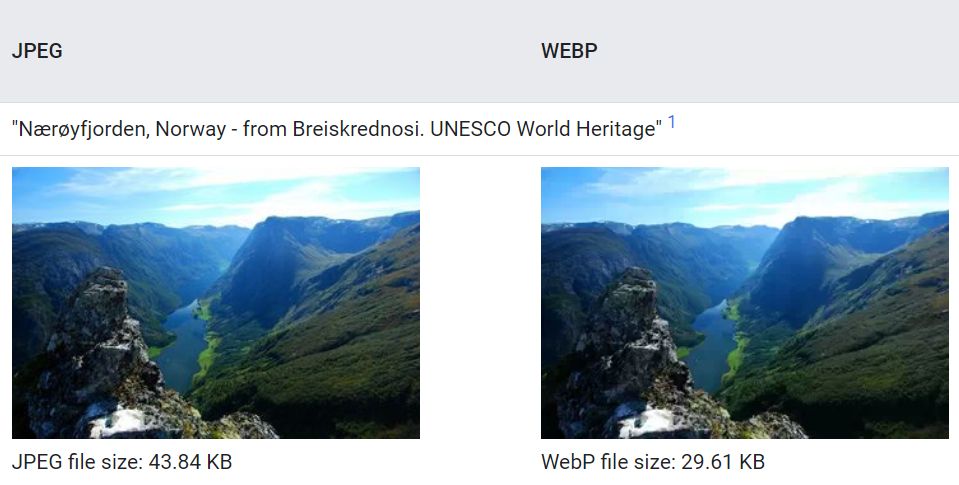

According to Google's studies, lossless WebP compresses 23-42% better than PNG while lossy WebP compression generates 25-34% smaller image files than JPG. However, some independent test results suggest that WebP compression is not always worth it — for example, Jim Nielsen found that lossless WebP files can be larger than their PNG equivalent optimized with the ImageOptim API.

Key Features of WebP

- a next-generation image format for raster images

- supports both lossy and lossless compression

- for lossy compression, it uses the keyframe encoding of the VP8 video format

- for lossless compression, it uses the WebP Lossless Bitstream specification

- 24-bit RGB color depth (like PNG and JPG)

- supports transparency and semi-transparency via the 8-bit alpha channel

- supports animations (see some examples by Colin Bendell)

- all modern browsers support it

Recommendations

- To reduce page weight, consider converting your JPG images to lossy WebP and PNG images to lossless WebP format.

- If you need to support old browsers, add the JPG or PNG version as a fallback.

- For lossless WebP conversions, run your own tests to see whether the additional complexity is worth the performance gain and whether you can achieve a similar result by optimizing your images in their current format.

Image: JPEG vs WebP comparison (credit: Google Developers, WebP Gallery)

Image: JPEG vs WebP comparison (credit: Google Developers, WebP Gallery)

AVIF (AV1 Image File) – Lossy and Lossless

The AVIF image format was released in 2019 by AOMedia (Alliance for Open Media) with the aim to achieve a better compression quality than WebP. Both its lossy and lossless versions use the AV1 video codec for compression. AVIF comes with advanced visual features that currently no other production-ready image format offers, such as depthmaps and overlays.

AVIF also supports three color depths:

- 24-bit (true color), which is equal to 8 bits/channel across the three RGB channels (red, green, blue)

- 30-bit (deep color), which is equal to 10 bits/channel

- 36-bit, which is equal to 12 bits/channel

This makes it possible to use color spaces beyond sRGB (standard RGB) such as HDR (High Dynamic Range) and WCG (Wide Color Gamut).

While AVIF was created to supersede WebP, performance tests have had some mixed results. The lossy version performs well on all tests (see some examples on Netflix Tech Blog, by Daniel Aleksandersen, and by Jake Archibald), however the lossless version is often outperformed by WebP and even PNG (check out this discussion on GitHub).

Key Features of AVIF

- a next-generation image format for raster images

- supports both lossy and lossless compression

- uses the AV1 compression algorithm

- supports 24-bit, 30-bit, and 36-bit color depths

- supports animations, alpha-channel transparency, depthmaps, and overlays

- support across all major browsers

Recommendations

- As AVIF's lossy version almost always outperforms JPEG and WebP, especially at low fidelity, consider converting your JPEG and WebP photos to AVIF format.

- Because of the poor test results of AVIF's lossless version, don't convert your PNG and lossless WebP images to AVIF, unless you want to use AVIF's visual features or your own performance tests show otherwise. Instead, optimize your existing PNG images or convert them to WebP.

Image: Compressing JPG to lossy AVIF with the Squoosh app

Image: Compressing JPG to lossy AVIF with the Squoosh app

SVG (Scalable Vector Graphics) – Vector (Which Is Lossless)

SVG is a vector image format that you can use on the web. It's been developed by W3C since 1999, and the first version was released in 2001. Each SVG graphic is composed of geometric shapes such as lines, curves, and polygons defined as vectors in a Cartesian coordinate system. As an SVG image consists of mathematical formulas (instead of pixels), you can increase or decrease its size without any loss of quality.

Even though browsers and vector image editing tools display SVG files as images, SVG is actually a text file that can also be edited as code. SVG files are usually more lightweight than their PNG equivalent (except for highly complex illustrations). As SVG uses the XML markup, it has a syntax similar to HTML.

Key Features of SVG

- an XML-based vector image format

- retains quality at any size

- supports the 24-bit sRGB color space (like PNG, JPG, and WebP)

- supports animations and transparency

- can be styled with CSS and programmed in JavaScript

- wide browser support

Recommendations

- Use SVG for line graphics, text-heavy images, logos, icons, background patterns, and vector illustrations.

- Don't use SVG for complicated graphics such as illustrations using hundreds of colors or artwork with fine details.

Image: A customizable SVG background in BGJar

Image: A customizable SVG background in BGJar

Recommendations to Choose the Best Image Formats for Your Website

Choosing the best image formats for your website depends on many things, such as your content strategy, the characteristics of your images, the browsers you need to support, the skills of your team, etc.

However, here are some pointers to help you choose:

If you don't want to serve images in next-gen formats (e.g. you pass the Lighthouse audit with your current images, and the performance gain wouldn't be much), but still want to find the best balance between performance and quality, use:

- JPEG for photos and photo-realistic illustrations (you can optimize them with a tool such as MozJPEG)

- PNG for screenshots and complex non-photographic illustrations, or instead of SVG if you don't want to use vector graphics

- SVG for icons, vector logos, illustrations with less complexity, text-heavy images, background patterns, and animations

- GIF for cartoon-style web graphics, grayscale photographs, and non-vector logos

If you want to serve images in next-gen formats to improve page load times and Core Web Vitals, start by replacing your JPEG images with the lossy version of WebP or AVIF. While AVIF is a bit less widely supported by browsers than WebP, its lossy algorithm has a better compression ratio and it offers more advanced features.

As the lossless versions of WebP and AVIF have had some mixed test results, it's not necessarily worth adding them, unless you want to use their other features, such as AVIF's support for non-standard RGB color spaces. It can be a good alternative to optimize your PNG images with a tool such as Oxipng or ImageOptim, or replace them with SVG wherever it's possible to use vector graphics.

If you have an image-heavy website, you can also consider using an image CDN, such as Cloudinary. These services automatically generate, select, and serve the most performant format and size for each image on your site.

Next Steps

Finding the best image format is just the first step of image optimization. There are many other best practices you can follow to improve image performance on your website, such as lazy-loading images, prioritizing them with Priority Hints, and serving responsive images.

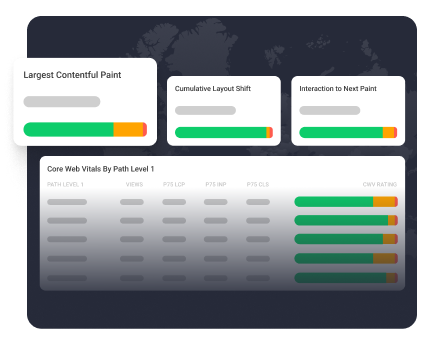

To decide whether you should serve images in next-gen formats, either run a Lighthouse test from Chrome DevTools, or use a frontend performance monitoring tool that accesses the Lighthouse API, such as DebugBear, which comes with tons of extra features compared to the default Lighthouse tool.

To get more insight into image performance on your website, run a free website speed test, check out DebugBear's interactive demo, or sign up for a free 14-day trial (no credit card needed).

Monitor Page Speed & Core Web Vitals

DebugBear monitoring includes:

- In-depth Page Speed Reports

- Automated Recommendations

- Real User Analytics Data