Render-blocking resources: they're the critical files that delay your page content appearing and can increase Core Web Vitals metrics like the Largest Contentful Paint.

Some of these files might be important, but they can add crucial seconds to your load times, damage your Core Web Vitals scores, and even incur penalties in your search rankings. In this article, we'll explain which files block rendering and how to eliminate their performance impact.

What are render-blocking resources?

Render-blocking resources are files or scripts that prevent any page content being rendered until they're fully loaded. While browsers typically request dozens or even hundreds of resources when displaying a page – including images, videos, stylesheet files, third party code snippets and more – only a handful of critical resources will block rendering completely. Let's take a look at an example.

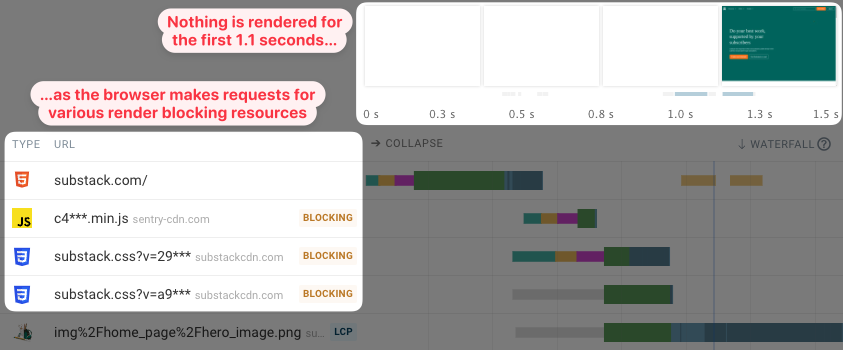

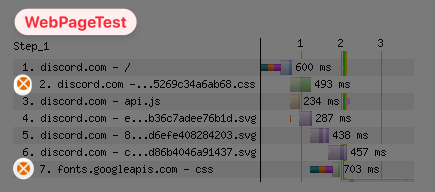

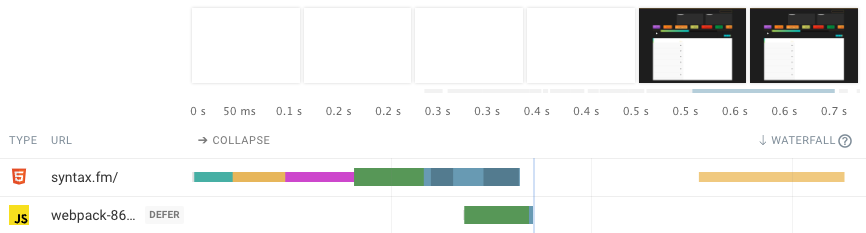

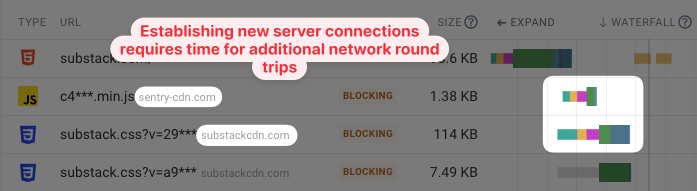

The screenshot below shows a rendering filmstrip and request waterfall for a website. While the request for the HTML document finishes after 600 milliseconds, the browser still shows a blank page at that point.

The browser only starts rendering the page once three additional resources have finished loading:

- A JavaScript file (

c4.min.js) - A CSS file (

substack.css?v=29***) - Another CSS file (

substack.css?v=a9***)

You can test your own website using the DebugBear page speed test.

What kinds of files are render-blocking resources?

The two most common types of render-blocking resources are:

- CSS files in the

<head>tag - JavaScript in the

<head>tag

Conversely, these common file types don't block all rendering:

- Images & videos

- Font files (TTF, EOT, WOFF, WOFF2, etc.)

- JavaScript in the

<head>tag with theasyncordeferattribute - CSS appearing late in the

<body>tag - JavaScript appearing late in the

<body>tag

These files can still block some specific page content from showing up. For example, text that relies on a web font may not render until after the font is loaded, and a JavaScript widget on the page won't render until the relevant script has run.

CSS stylesheets and JavaScript files can block rendering. Resources that are needed to display page content form the critical rendering path.

How do render-blocking resources impact site speed metrics?

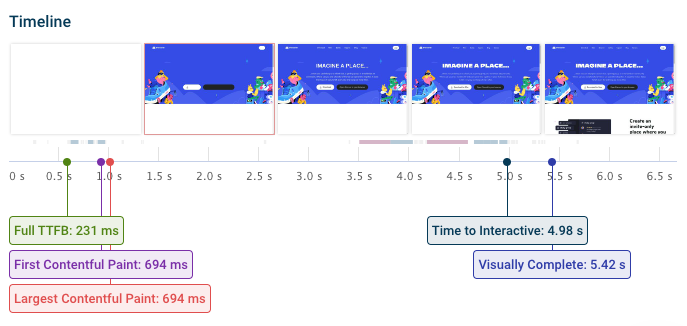

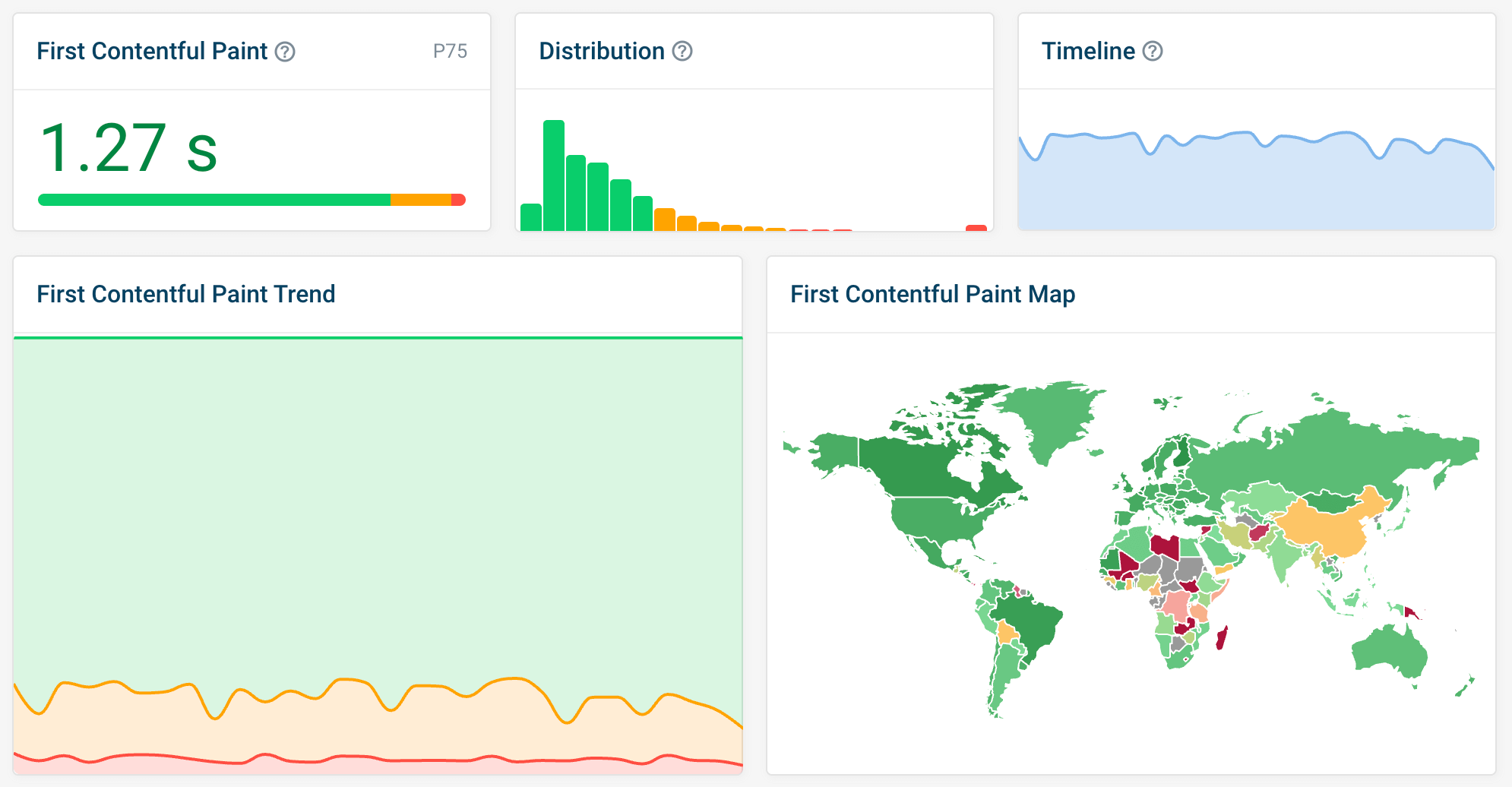

Rendering blocking resources delay rendering milestones like the First Contentful Paint and the Largest Contentful Paint.

The severity of a render-blocking resource's impact on page speed depends on a few factors:

- The size of the resource being downloaded

- Whether a new server connection is required to load the resource

- Whether there's a chain of render-blocking resources that delays the download starting (see below for more on this!)

How render-blocking resources affect Core Web Vitals and SEO

As Largest Contentful Paint (the moment the biggest piece of content appears in the browser window) is a Core Web Vitals metric, we need it to happen as soon as possible. By definition, the First Contentful Paint (the moment any piece of content is displayed) is a milestone on this page loading journey.

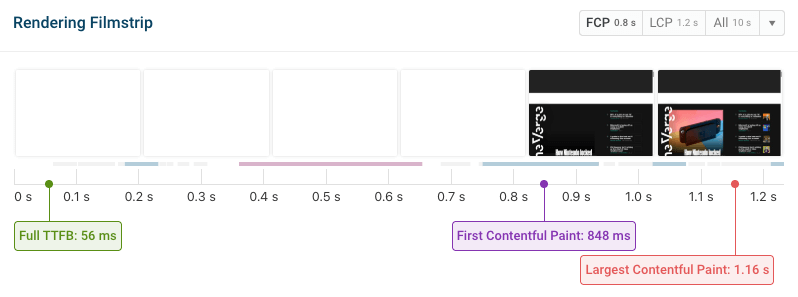

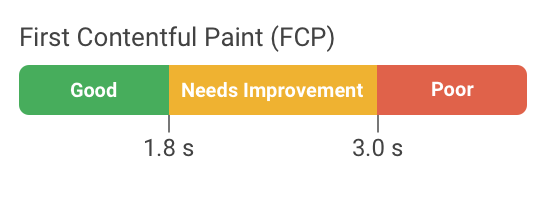

Although FCP isn't a 'core' web vital, it's still tracked in Google's CrUX report, and needs to happen within 1.8 seconds to be considered 'good.' So every millisecond matters!

Don't forget, you'll need at least 75% of your users to have a good experience to avoid penalties in search results, so optimizing your page performance is crucial for SEO purposes.

If your page has few render-blocking resources to optimize but is still loading slowly, you might have an issue with how quickly your server is responding – the so-called Time to First Byte.

On the other hand, if your first pieces of content are loading quickly but then jumping around the page as other elements load, learn more about fixing layout shift issues.

What are render-blocking request chains?

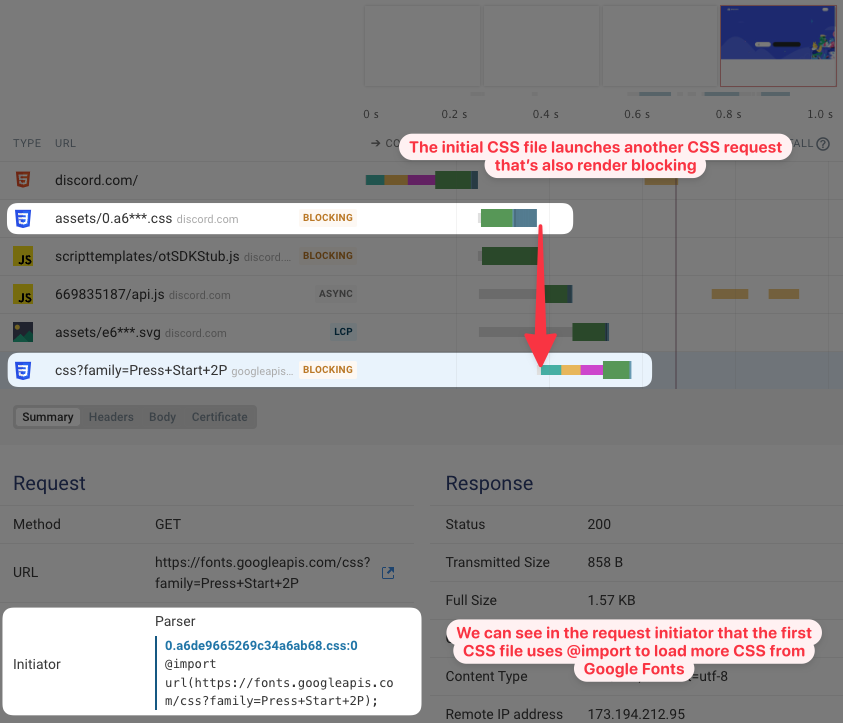

A render-blocking request chain happens when a render-blocking resource triggers a request for another render-blocking resource.

In this example, the render-blocking CSS file is loaded after 400 milliseconds. But that CSS file uses @import to reference another CSS file. This file also needs to be downloaded before the page renders after 700 milliseconds.

The longer these chains are, the bigger the performance impact will be.

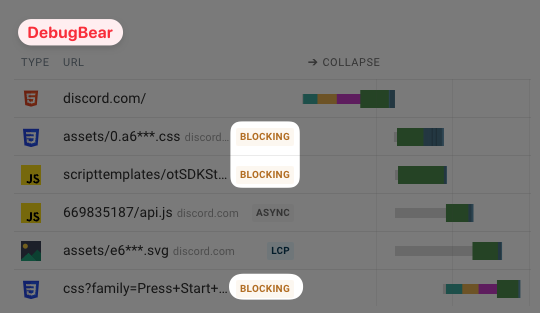

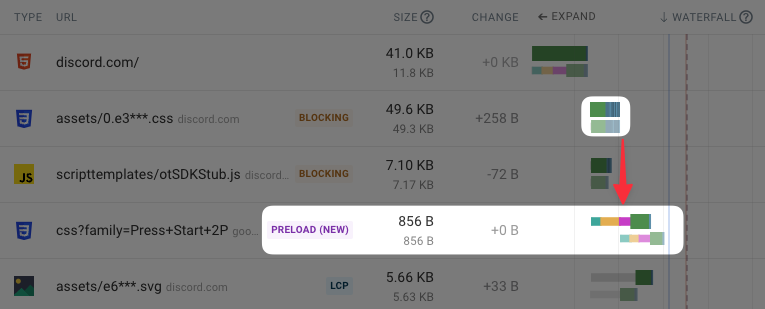

Notably, the second CSS also requires a new server connection to be established to fonts.googleapis.com. Because of this, the request will take longer than if another resource from discord.com had been loaded.

You can see our founder Matt explore a request chain in this video:

What does parser-blocking mean?

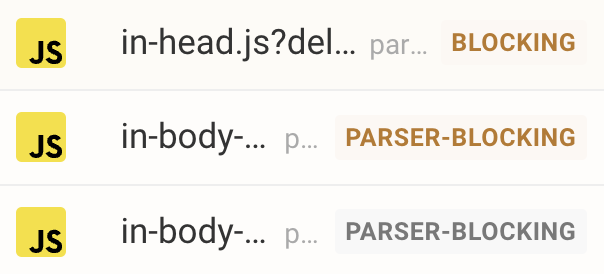

Scripts and stylesheets referenced in the head always block all rendering (at least if they are loaded synchronously). These are called initial render-blocking.

But what about resources referenced in the body? Chrome marks those as in_body_parser_blocking. Whether they block render depends on where in the body they appear.

If they are placed at the end of the body tag, then parser-blocking scripts don't block rendering. But if a parser-blocking script appears at the top of the body tag, the script will block rendering.

How to identify render-blocking resources

Many articles say that JavaScript and CSS files in the head are render-blocking. That's a good heuristic, but that's not always the case (for example, if the async attribute is used).

You can use different tools to identify render-blocking requests on your website:

- DebugBear

- WebPageTest

- Chrome DevTools

- Lighthouse

Let's take a look at how different tools report render-blocking requests.

Explore our post Visualize your Website's Blocking Scripts to learn more about how to identify render-blocking requests.

DebugBear

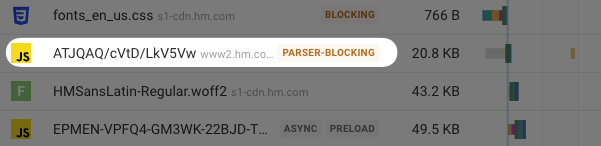

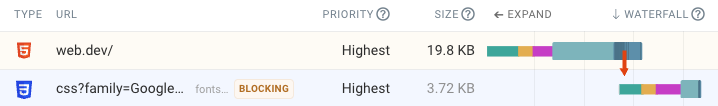

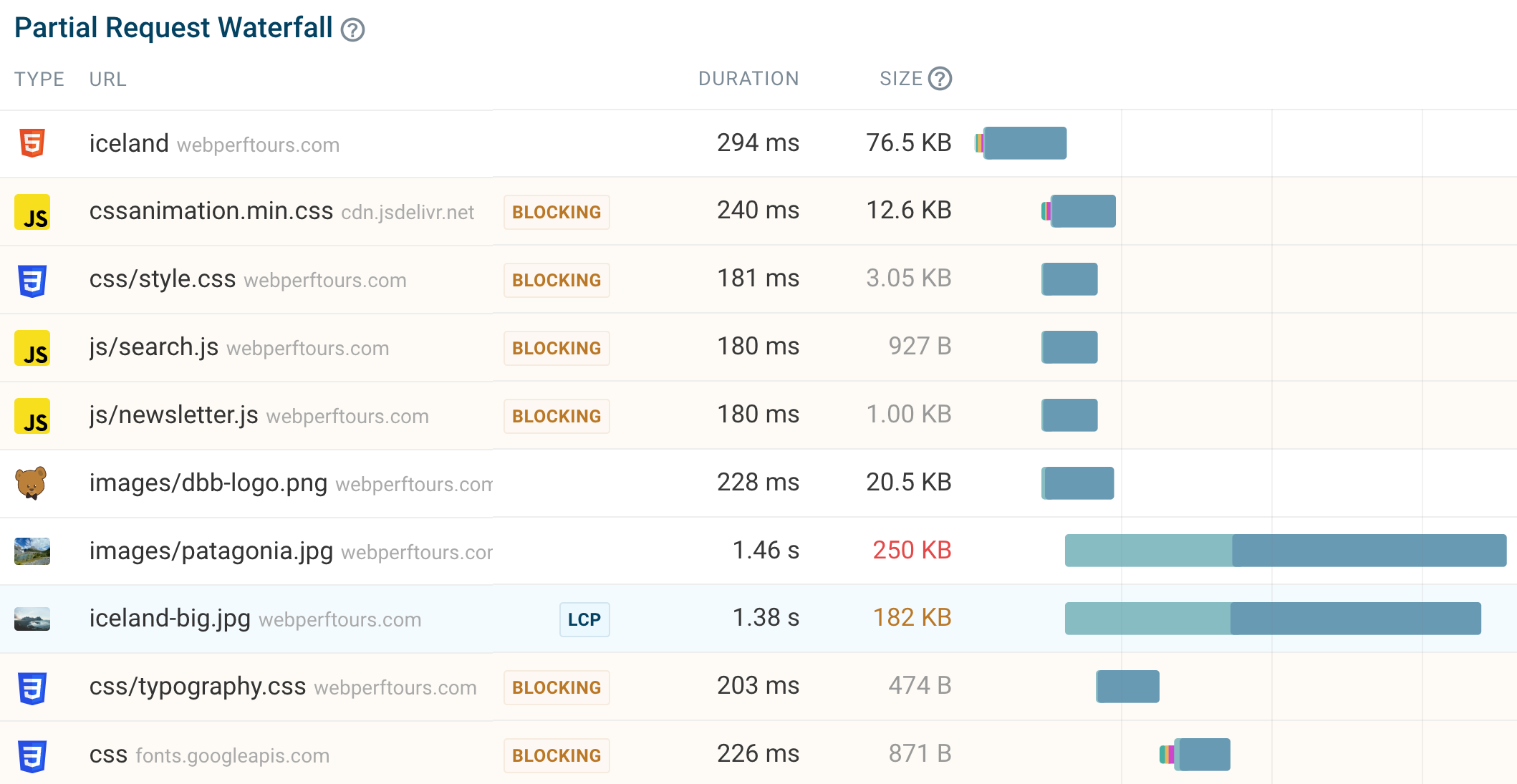

DebugBear test results show a request waterfall where all render-blocking resources are marked with a "Blocking" badge.

Blocking resources in the HTML body

Parser-blocking resources in the HTML body are also highlighted. Whether they impact page speed depends on where in the HTML the tag is located.

The color of the badge indicates to you which resources you should prioritize for optimization.

- An orange parser blocking badge means that the resource comes before the main page heading (the

<h1>tag) and could block rendering of important page content. - A gray parser blocking badge means that the resource comes after the main page heading. Depending on where this resource is, it may not block rendering of important page content.

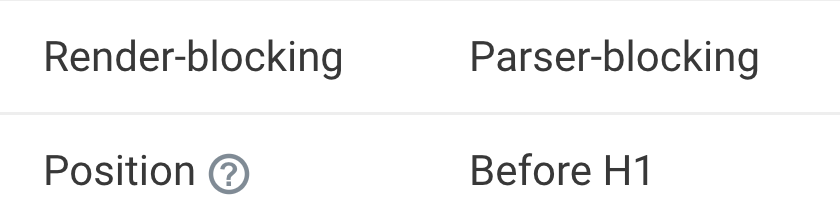

When you open up a resource from the DebugBear request view, you get extra metadata including the render-blocking status, and the position of the resource in the document relative to the <h1> tag.

WebPageTest

You can test your page with WebPageTest and view the request waterfall in the test result. It marks render-blocking requests using an orange badge with an "x" marker.

Chrome DevTools

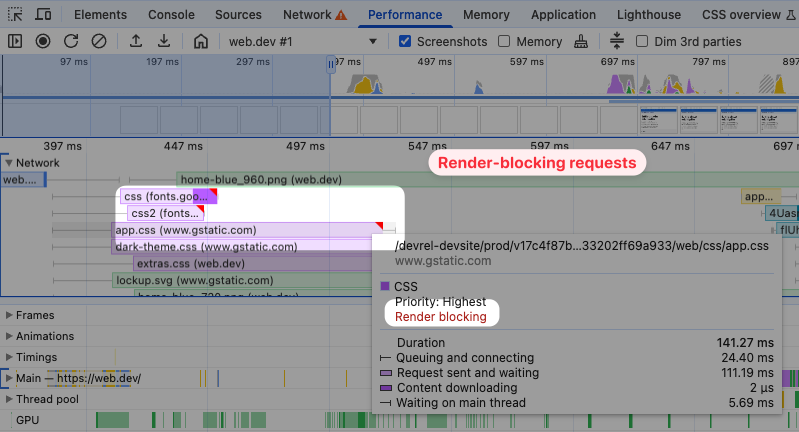

The performance profile in Chrome DevTools includes a lane showing network requests.

Render-blocking requests are marked with a red rectangle on the right of the request bar.

Lighthouse audit: eliminate render-blocking resources

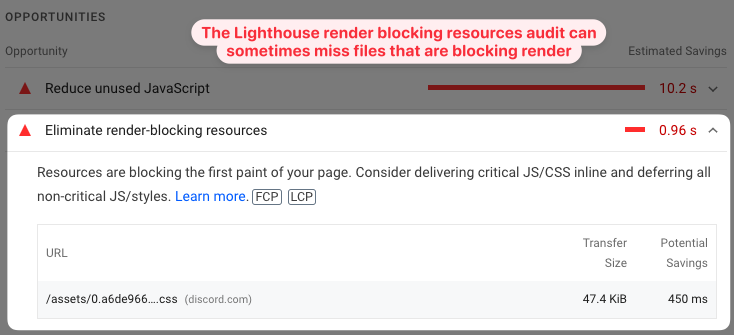

The Lighthouse report shown on PageSpeed Insights also contains an "Eliminate render-blocking resources" audit.

Lighthouse can sometimes miss render-blocking files. For example, in the Discord example the Google Fonts CSS is incorrectly not shown as render-blocking.

Eliminating render-blocking resources

Now for the important part – how to eliminate, defer, bypass, compress, or otherwise solve the problem of render-blocking resources.

The steps you need to take to remove a render-blocking request depends on the type of resource that's being loaded.

You might need to change script tags to load asynchronously, or inline critical CSS. Let's start with JavaScript files.

Got a WordPress website? Check out our guide to eliminating render-blocking resources in WordPress.

Render-blocking script tags

By default, the browser goes through the document from top to bottom. JavaScript code is run synchronously one script after the other.

For example, in this case the browser will first run chat.js and then analytics.js. The h1 tag is only shown after running the scripts.

<script src="chat.js"></script>

<script src="analytics.js"></script>

<h1>Hello world</h1>

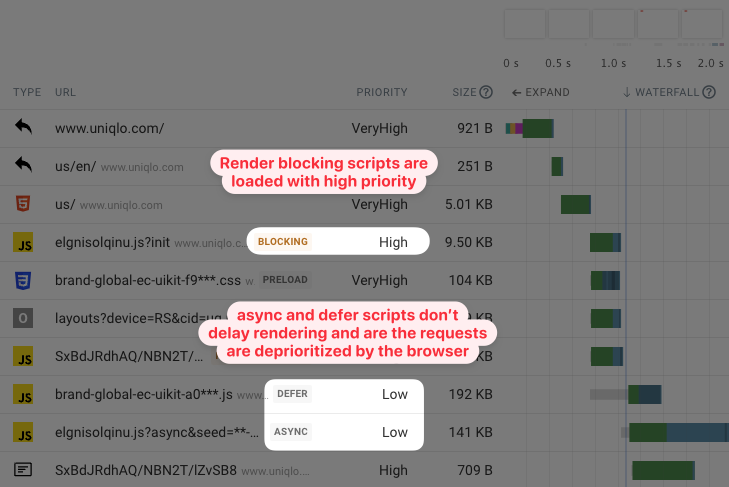

However, many scripts don't need to be render-blocking and can be run asynchronously. You can achieve that using the async attribute.

<script src="chat.js" async></script>

<script src="analytics.js" async></script>

<h1>Hello world</h1>

Now the browser will still start loading the JavaScript files as soon as possible, and run them as soon as they are downloaded. But in the meantime, rendering the h1 will no longer be blocked.

Also, if analytics.js finishes loading before chat.js, then analytics.js will run without first waiting for the chat widget code. If you want to maintain the order of execution you can use the defer attribute, which defers JavaScript execution until after the HTML document has been fully parsed by the browser.

This waterfall chart demonstrates the impact that async and defer have on page load behavior.

Render-blocking CSS

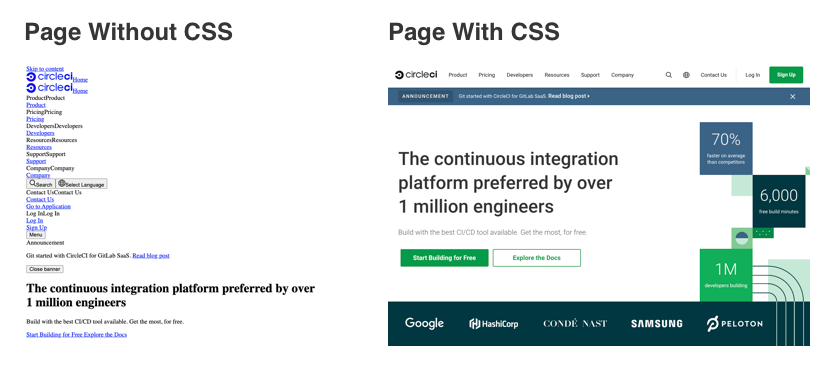

Reducing render-blocking stylesheets is harder than reducing render-blocking scripts, as a page will often look very different if stylesheets are missing. If you made an important stylesheet load asynchronously, you'd get a flash of unstyled content (FOUC).

While loading key CSS files asynchronously is not an option, loading stylesheets for third party code can be more viable, for example, if you have a third party widget that's only used further down on the page. In that case, updating the styling later on is acceptable. Another candidate for asynchronous CSS loading would be a stylesheet that only loads font references but does not affect the page layout.

Let's say you have this stylesheet in your HTML:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="widget.css" />

This way, widget.css will block rendering. To load the stylesheet asynchronously, you can initially set the media attribute to print. Then, when the CSS file has loaded, you change it to all to apply the styles to the page.

<link

rel="stylesheet"

href="widget.css"

media="print"

onload="this.media='all'"

/>

Inlining critical CSS

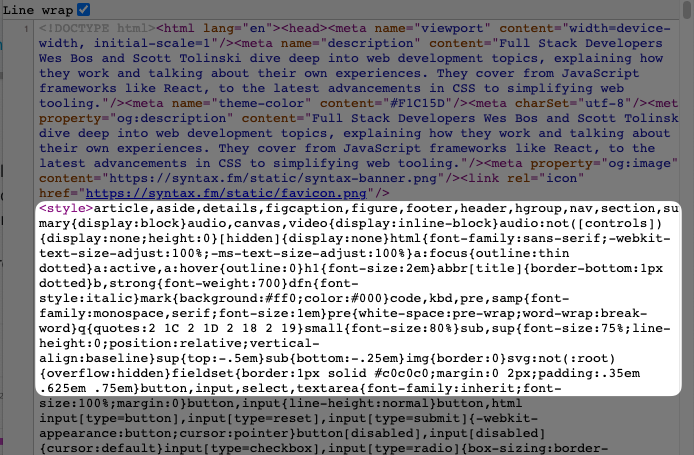

Another way to remove render-blocking CSS files is to embed the styles directly in the HTML document. This will increase the size of the HTML, but it can be a great solution for small CSS files under 10KB.

Here's an example website where render-blocking CSS is inlined into the page HTML. The page renders immediately after the document is loaded.

When we look at the page HTML we see a large inline style tag.

The downside of this approach is that the CSS has to be downloaded again with every HTML request, while a separate CSS file could have been cached. How bad this is depends on the amount of CSS being inlined.

Monitor Page Speed & Core Web Vitals

DebugBear monitoring includes:

- In-depth Page Speed Reports

- Automated Recommendations

- Real User Analytics Data

Inline render-blocking Google Fonts CSS

Typically, Google font styles are loaded using a render-blocking CSS request. Since the resource is hosted on Google's domain, that also means a new server connection is required, causing the request to take longer.

To fix that, you can take the contents of Google's CSS file and inline it directly in your HTML code or into another CSS file hosted on your own server.

Google provides a number of unicode ranges in the CSS. Usually, you'll just need one or two to render content on your website, for example, latin and latin-ext.

<style>

/* latin */

@font-face {

font-family: "Google Sans";

font-style: normal;

font-weight: 400;

font-display: swap;

src: url(https://fonts.gstatic.com/s/googlesans/v62/4UasrENHsxJlGDuGo1OIlJfC6l_24rlCK1Yo_Iqcsih3SAyH6cAwhX9RPjIUvbQoi-E.woff2)

format("woff2");

unicode-range: U+0000-00FF, U+0131, U+0152-0153, U+02BB-02BC, U+02C6,

U+02DA, U+02DC, U+0304, U+0308, U+0329, U+2000-206F, U+20AC, U+2122,

U+2191, U+2193, U+2212, U+2215, U+FEFF, U+FFFD;

}

</style>

Google Fonts provides some advanced features, for example, to serve alternative font formats to older browsers. However, today most browsers support the WOFF2 file format, so this dynamic functionality isn't as important.

How to reduce the performance impact of render-blocking resources

Often not all render-blocking resources can be eliminated. But you can still reduce the impact they have on performance.

Reduce file size

Downloading large files takes longer than downloading small files. Therefore, reducing the size of critical requests can speed up your website.

There are a few ways to reduce file size:

- using better content encoding, e.g., switching from gzip to brotli

- making sure only the most important content is included in blocking files, and additional content can then be loaded later on

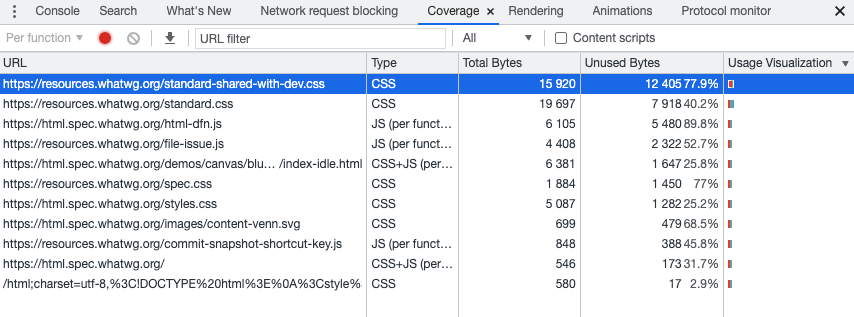

The Chrome DevTools Coverage tab can help you identify and remove unused CSS and JavaScript code on your page.

Reduce resource competition

Network connections can only provide a limited amount of bandwidth, so check if other resources are competing with the render-blocking requests.

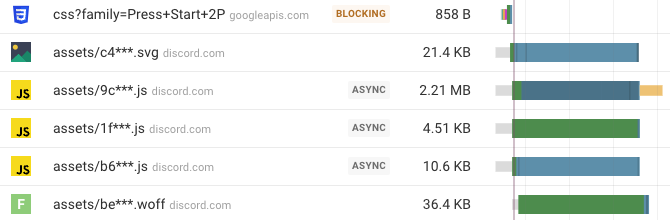

Here's an example of what resource competition looks like in a waterfall chart. The c4***.svg image is quite small, only 21 kilobytes. But the browser is allocating bandwidth to the JavaScript file below it, loading over 2 megabytes of data. So the SVG only finishes loading once the JavaScript resource has finished loading.

Reuse server connections

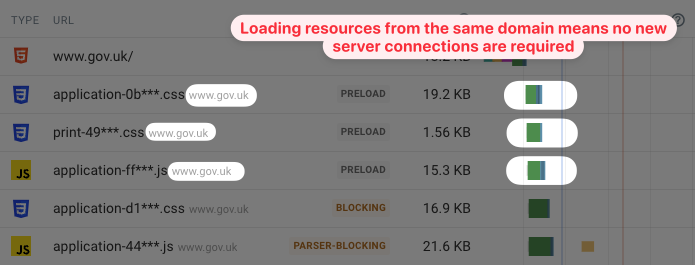

Connecting to a new server requires the browser to do a DNS lookup, establish a TCP connection, and enable a secure SSL connection. Each of these steps requires at least one round trip on a network. The browser can only start making the HTTP request once the connection is established.

For example, the Substack website is located on substack.com, but then loads additional render-blocking resources from sentry-cdn.com and substackcdn.com.

In contrast, the gov.uk website loads all resources from gov.uk and can therefore reuse the existing server connection.

Reduce request chaining

Render-blocking request chains happen when a render-blocking resource starts loading another render-blocking resource.

CSS @import

We saw this briefly earlier on in this article when we looked at how to identify render-blocking files. The Discord homepage used @import to load a stylesheet from Google Fonts.

@import url(https://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Press+Start+2P);

The browser first needs to load the Discord stylesheet to discover the Google Fonts file. We can use a preload resource hint to help the browser discover the resource sooner.

<link

rel="preload"

as="style"

href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Press+Start+2P"

/>

Adding this hint in the document HTML means the browser will start loading it without first waiting for the Discord CSS file.

This waterfall shows the page requests without the preload and then with the preload. After adding the preload the start time of the fonts CSS requests shifts to the left.

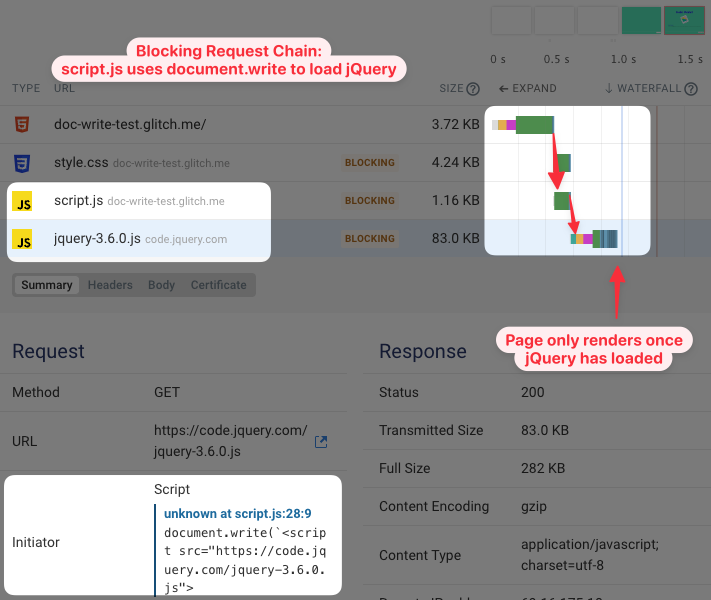

document.write

document.write can cause similar issues for JavaScript as @import does for CSS. If a render-blocking script synchronously creates a new script element with document.write then the new JavaScript file will also be render-blocking.

This waterfall shows an example where script.js synchronously adds jquery-3.6.0.js to the page and thus delays rendering.

Again, this could be fixed by using a preload hint. Putting the script tag directly into the document HTML, instead of using document.write, would also address the issue.

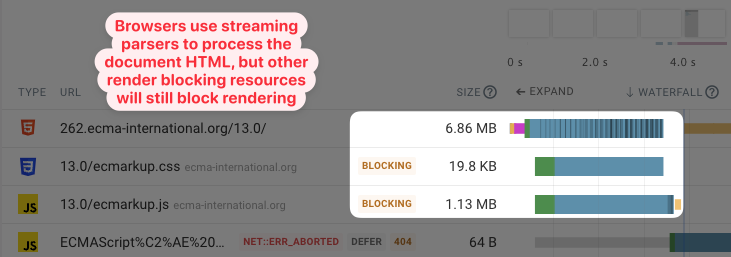

Is the HTML document request render-blocking?

The HTML document is at least partially render-blocking, as the browser can't show the page without knowing what its contents are. To find that out, the web server needs to start sending the HTML code to the client.

Therefore, a slow Time to First Byte (server response time) will make your website render more slowly.

However, browsers use streaming parsers that start processing the HTML as soon as it comes in, rather than waiting until the full document has been downloaded. Therefore, pages can start rendering before the document has finished loading.

This example shows that the other resources referenced in the HTML document start downloading before the HTML request has completed.

In this case, we don't see the page rendering before the completion of the document request though. That's because downloading the page HTML is a high priority task for the browser, so the other render-blocking resources have to compete with that. Due to the focus on loading the HTML, loading the CSS and JavaScript code for the page only happens after the HTML download is complete.

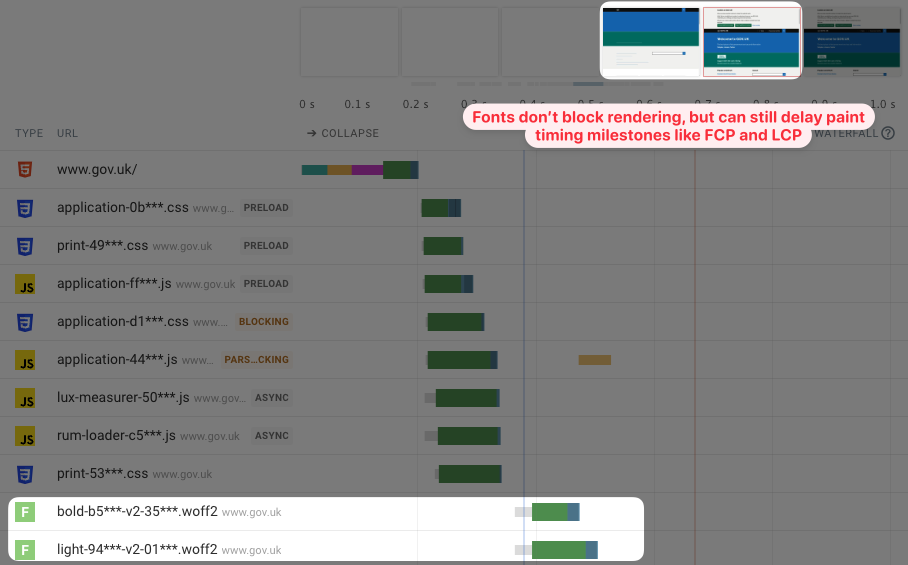

Are web fonts render-blocking?

Web fonts don't block rendering of the page, but they can block rendering of the text itself. How text renders before fonts are loaded is specified by the font-display CSS property.

Waiting for web fonts can slow down your First Contentful Paint if no other content is rendered on the page. If your text is still hidden but an image has rendered somewhere on the page, then web fonts won't make your FCP worse.

The Largest Contentful Paint will be impacted if the LCP element is a text node using a web font.

Are images render-blocking?

Images are not render-blocking. They can delay metrics like the Largest Contentful Paint, but the rest of the page will still render fine even if the browser is still downloading an image file.

Why isn't my page rendering after all render-blocking resources have loaded?

Sometimes the request waterfall suggests that all render-blocking requests have finished, but the filmstrip will still show a blank page. This can have a few reasons.

Is content being hidden with CSS?

Some A/B testing tools set the body opacity to 0 to avoid flicker, delaying when the page renders.

Single page apps

Some sites are pure single page apps with no server-rendered content. Instead, client-side rendering is needed before content appears. In those cases, even if rendering isn't blocked, there isn't any content to render until the JavaScript application has been loaded and has run.

To fix this, consider rendering a header on the backend or at least embedding a loading spinner in the page HTML to indicate the browser is waiting for the JavaScript app to load.

Parser blocking resources

As mentioned above, synchronous scripts or stylesheets in the body block all rendering of content below that tag. This isn't a problem if the tags are placed at the end of the body tag, but if they appear before important content then rendering will be delayed.

Fixing render-blocking resource issues in Wordpress

If your site is on WordPress, check out our full guide. A few top tips are:

- Choose your WordPress theme with performance in mind: When picking the right theme for your site, look beyond the superficial design and ensure that it loads quickly, too! The right theme will eliminate many render-blocking resources through practices like code minification, bundling, and deferring non-critical resources. Examples include Astra, GeneratePress, and Blocksy.

- Watch out for plug-ins slowing things down: Examine "content plugins" that add widgets, forms, pop-ups, or other front-end elements to determine if they're still being used and what performance impact they have. Consider replacing poorly-performing plugins with lighter alternatives.

- Speed things up with a performance optimization plugin: Try installing a plug-in like WP Rocket, Perfmatters, or Autoptimize to eliminate render-blocking resources through features like removing unused CSS, deferring non-essential scripts, and inlining critical CSS. Only use one plugin to avoid conflicts.

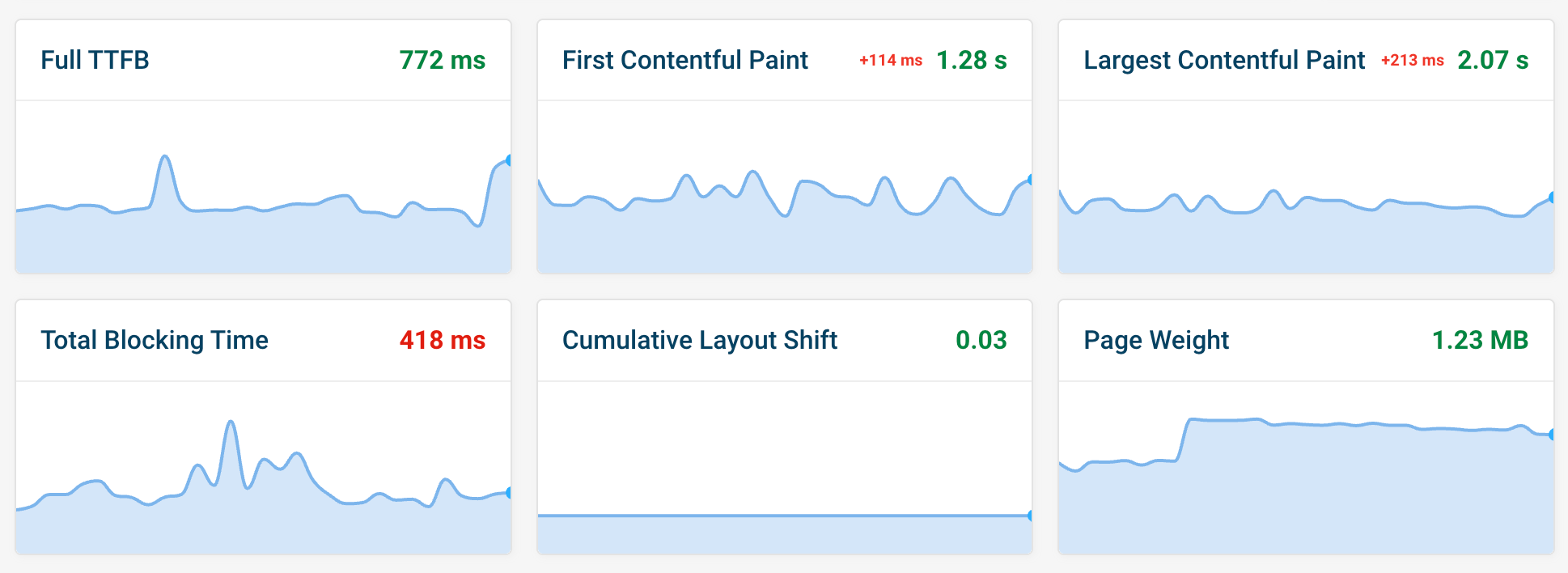

Monitoring page speed

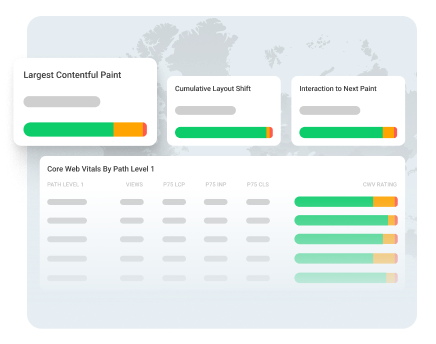

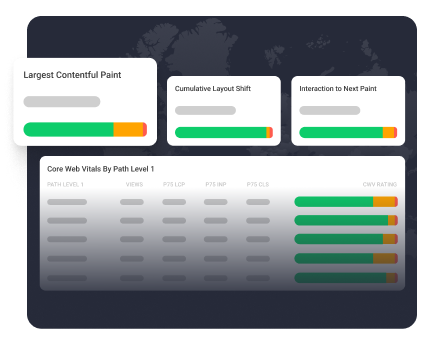

DebugBear can help you detect render-blocking resources, optimize your site speed, and monitor Core Web Vitals and other performance metrics over time.

Once you've reviewed your metrics you can investigate test results in depth:

- Identify render-blocking resources

- View request priorities

- Optimize image loading

Real user monitoring

DebugBear also offers a real user monitoring solution that helps you visualize render-blocking resources and other performance issues on your website - as experienced by your real users.

You can also see a real-world network request waterfall for each page view on your website.

Monitor Page Speed & Core Web Vitals

DebugBear monitoring includes:

- In-depth Page Speed Reports

- Automated Recommendations

- Real User Analytics Data